Dan Callaghan’s brother, William, was also an admiral in the Navy and served as the commander of the U.S.S. Missouri, the battleship on which Japanese representatives surrendered to the Allies in Tokyo Bay to mark the end of the war. After attending SI, he graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1918 and served in World War I on a destroyer. In 1936, he received his first command, that of theU.S.S. Reuben James (later sunk by a German U-Boat in 1940), and later joined the staff of the Chief of Naval Operations in 1939, where he served as logistics officer for the commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet, receiving the Legion of Merit for his efforts.

He commissioned the Missouri in 1944 and led it in operations against Tokyo, Iwo Jima and Okinawa. During the Battle of Okinawa on April 11, 1945, Callaghan’s ship came under kamikaze attack. Fortunately, the 500-pound bomb aboard the plane failed to detonate, but the pilot was killed instantly when his plane crashed into the battleship.

Crewmembers put out the fire around the plane and found the broken body of the Japanese pilot lying on the deck. The crew felt anger and outrage, but Callaghan ordered them to prepare the pilot’s body for burial with military honors, “an unprecedented act for an enemy in time of war.” Some of the crew grumbled, but others respected Callaghan for doing the right thing. Crewmembers worked at night to create a Japanese flag to drape over the body, and the ships’s chaplain offered the prayer, “Commend his body to the deep,” while the Missouri’s crew saluted and an honor guard fired their rifles to honor this fallen pilot.9

“Interestingly, during a September 1998 reunion of former U.S.S. Missouricrewmembers at the battleship’s new home in Pearl Harbor, many of those who served in World War II told members of the Association that, in retrospect, they felt Captain Callaghan acted correctly,” according to Patrick Dugan of the U.S.S.Missouri Memorial Association.10

Callaghan went on to serve as commander of Naval Forces in the Far East during the Korean War and retired in 1957. He died July 8, 1991, at the age of 93. On April 12, 2001, he was honored in memoriam at a ceremony aboard the Missouri, docked at Pearl Harbor,to commemorate the respect he paid to the Japanese pilot. Since kamikaze pilots wore no identification, the Japanese Navy narrowed the identity of the pilot to three possibilities, and descendents of each of these families attended the ceremony. One family brought water taken from the area where a U.S. submarine had recently surfaced, accidentally sinking a Japanese fishing boat, and that water was poured into Pearl Harbor from the Missouri.

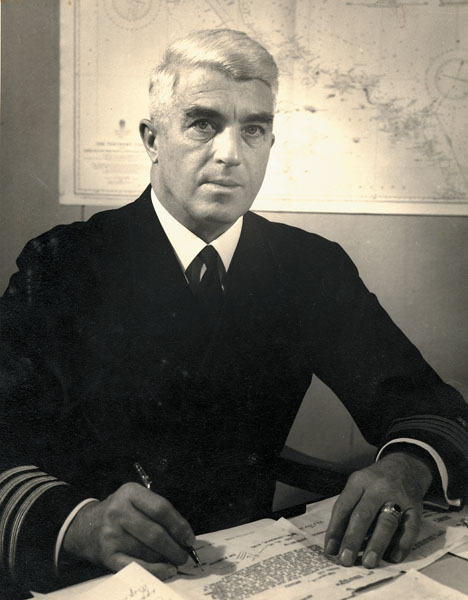

Above: Admiral Daniel Callaghan (1907) and (below) Admiral William Callaghan (1914).

By Caitlin Callaghan ’99

This article is adapted from a speech Caitlin Callaghan ’99 gave at the annual Admiral Callaghan Society awards dinner on April 30, 2015.

When I was growing up in San Francisco, I heard lots of stories about the two Admiral Callaghan brothers, Daniel (SI 1907, center column) and William (SI 1914, right column) — or Dan and Bill, as they liked to be called.

I knew Bill, who was my great-grandfather. He died when I was 10. I never had the opportunity, however, to meet Dan, who received posthumously the Medal of Honor. Dan’s story is known well at SI these days: The admirable naval career that culminated in his heroism at the World War II Battle of Guadalcanal, where he was killed on the bridge of the U.S.S. San Francisco, lives on through the school’s Admiral Callaghan Society. Bill, in contrast, survived World War II. He ultimately retired from the Navy as a Vice Admiral, and his last appointment was as Commander of the U.S. Naval Forces, Far East.

Dan and Bill were seven years apart in age, but they were extremely close throughout their lives. They were the grandsons of two Gold Rush pioneers and grew up in San Francisco and in Oakland at the turn of the 20th century. Their uncle James Raby, who was also an admiral, inspired them to attend the Naval Academy and pursue their lives in the Navy. A further motivation for Bill was the sight of President Theodore Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet entering San Francisco Bay in 1908. Years later, in 1917, his midshipmen summer cruise would take place on the U.S.S. Connecticut, which was one of the Great White Fleet ships he had seen.

When the U.S. officially entered World War II, Dan and Bill were each in the Pacific. Bill was based at Pearl Harbor, where he was assigned to the staff of Admiral Chester Nimitz, who was then the commander in chief of the Pacific Fleet.

The Guadalcanal campaign began in August of 1942, when the Allies landed in the Southern Solomon Islands. Throughout the next three months, there were about 10 battles — both on land and at sea — between the Allies and the Japanese for control of the island of Guadalcanal itself, before the massive naval battle that took place in mid-November.

The writer James Michener, who was called to active duty as a naval historian during the War, wrote that in its aftermath, the name Guadalcanal became “one of the blood-honored in American history.”

For the Japanese, the name proved simply bloody — ominous, and without the luster of victory. After they ultimately retreated, a Japanese commander wrote, “I had 30,000 of the finest men. Ten thousand were killed. Ten thousand starved to death. Ten thousand were evacuated, too sick to fight.”

In October of 1942, there was a lull in the fighting on Guadalcanal. Admiral Nimitz and a few members of his staff, including Bill, flew down from Pearl Harbor. They first stopped in the capital of New Caledonia, another island in the South Pacific. This was the Allies’ deployment spot for the Solomons.

In New Caledonia, Dan and Bill were briefly reunited. It was fortuitous that their paths crossed at all. As the Allies struggled to uproot the Japanese from the Solomons, Dan’s time was split between New Caledonia and Auckland, New Zealand. Bill later reported that Dan seemed tired and worn out. This was likely the last time the brothers ever saw one another.

From New Caledonia and his brother, Bill flew with Nimitz to Guadalcanal. The intent was to assess the general situation the Allied forces were facing.

Bill wrote a letter to his son, Cal, about what he saw on Guadalcanal. Cal was my grandfather. At the time, he was 17 years old. He writes, “I wish you could have been here to see these fighting marines. They weren’t all dressed up as you see them in pictures on parade.… But living in fox holes and slit trenches isn’t very conducive to a natty appearance.… All of them looked like the tough, hard fighting men they are.”

Bill then describes what he saw beyond the marines’ makeshift quarters. “Just in front of the advanced lines were the barbed wire defenses. No [Japanese] were hanging on them limp and lifeless, but I had missed that scene by only a few days.”

Bill continues: “We were all set for an air raid the day I was there. [The Japanese planes] were reported on the way about two hours before noon. We got a grandstand seat in a palm grove to watch the show, but no more of [the planes] appeared. Just as well I guess, for the Marines told us it was no picnic to watch the bombs drop and wonder whether they are intended for you.”

He then writes that he is sending a souvenir for Cal: “It is some of the [Japanese] paper money, which they brought along with them to use in the conquered territory. Since the Solomons were under the control of the British, you will note that the face of the currency is stamped with the familiar units of British money — the shilling.”

Bill describes the trucks the Japanese left behind — some with Chevrolet parts bought in the U.S. before the war — and a dinner of captured Japanese rice and hearts of palm. In closing, he tells Cal to ask his mother if she knows what a “hep kat” and a “zoot suit” are, because he wants to “check on her acquaintance with things of the day.”

From the distance of more than 70 years, I find it hard to interpret the somewhat lighthearted tone of this letter. Maybe it’s because Bill wrote it to his teenage son. Maybe it’s because at that point Bill had served in the Navy for several years and was more inured to its dangers than the average letter writer.

Regardless, the tenor of a letter he wrote a few weeks later stands in stark contrast. Bill was back safely in Pearl Harbor on the night of Nov. 13, 1942. But because he was on Nimitz’s staff, he knew that on that day, Dan had been somewhere on Iron Bottom Sound back at Guadalcanal, in the middle of a horrific battle.

That evening, Bill wrote several pensive lines to his wife, Helen, my great-grandmother. He begins the letter with these words:

“I am terribly worried about Dan. Even before this reaches you the worst news may [have] come.… Of course, I can’t tell you anything about what he has been doing, except to say that he has been in a battle.… From what information is at hand, there is every reason to believe that he is either dead or seriously injured.… I suppose I’ll know by tomorrow, but ever since yesterday, the suspense has been terrible.”

Bill tries to make the letter a little more upbeat, asking his wife if people like “the opening of the second front in Africa” and commenting that “the poor old French seem to be getting it from both their enemies and their friends.”

But he closes the letter with these words: “Maybe I am unduly alarmed [about Dan], as there is nothing positive yet. Just a piecing together of certain facts which are indicative of what may be. So let us [keep] hope until I let you know to the contrary.”

Bill’s suspicions, however, were confirmed. Dan had been killed. By many accounts, Dan knew that he and his men would likely perish before the battle even began.

Guadalcanal was a powerful and much-needed victory for the U.S. It was also a devastating loss for the Callaghan family. My grandfather, Cal, who was also very close to his Uncle Dan, learned that Dan had been killed when he was riding the streetcar home from school in Washington, D.C. He saw Dan’s name in a newspaper headline that a fellow rider was reading.

When the U.S.S. San Francisco sailed home to its namesake city that December, one of the first people to board the ship was the father of Dan and Bill, who was my great-great-grandfather. A photographer from the Oakland Tribune captured their father’s drawn and heavy face as he heard firsthand the account of the battle and his son’s death. It was published on the front page, right underneath the photos of the cruiser, with all surviving hands on deck.

For some time following Guadalcanal, Bill continued to serve on Nimitz’s staff. Then he became the first captain of the U.S.S. Missouri. The Mighty Mo supported the invasion landings of Iwo Jima in the late winter of 1945 and then set course for Okinawa.

As I write, it is exactly 70 years since the Battle of Okinawa took place. The goal, if the Allies were victorious, was to use Okinawa as the base for an invasion of the mainland of Japan. The battle ultimately became one of the bloodiest in the Pacific, lasting for almost three months. Between the Allies, the Japanese and the local civilians, nearly 300,000 people died. It was also the battle in which the Japanese first unleashed kamikazes in coordinated attacks on Allied ships. Several days after the battle began on April 1945, a kamikaze in a Japanese Zero fighter took aim on the U.S.S. Missouri.

The pilot approached the ship low, just a couple dozen feet above the water. He flew towards the ship’s starboard side, from the stern, probably in the hopes of evading antiaircraft fire.

It is likely that the pilot intended to pull his plane up at the last minute and crash it into the battleship’s superstructure, but before he could do so, the left wing of the Zero grazed the deck of the ship. The plane spun onto the deck and broke in half.

Instantly, the deck was covered in the flames of burning gasoline. Debris splattered all across the stern. Fortunately, however, the part of the plane that held the 500-pound bomb did not detonate. That half, instead, had fallen into the sea.

The Missouri crew put out the fire. Then they turned the hoses to wash the remains of the dead pilot overboard.

They were told to stop.

Bill, their commanding officer, had sent down orders to prepare the pilot for a full military burial at sea with honors.

Bill believed that the pilot, just like the members of the Missouri crew, had performed the task his country had asked him to do. It’s been said that he spoke to the crew over the ship’s loudspeaker system and remarked upon the pilot’s duty and sacrifice.

The pilot’s remains were brought into sickbay. A crewmember stitched a makeshift Japanese flag. The following morning, the pilot received that full military burial, complete with six pallbearers and a volley of rifle fire.

From Bill’s perspective, his decision was not a difficult one to make, and for the rest of his life, he never wavered on this point. However, his decision still rankles people today. After all, it’s clear that the intent of the kamikaze pilot was a fatal one for the crewmen of the Missouri.

Just 14 years ago, one former crewmember said this to a newspaper reporter: “Most of the crew said that they should have put [the kamikaze] in a bag and thrown him over the side.” Another, a former gunner, said this: “It’s sort of a kick in the pants. If that kamikaze had made it another 100 feet, I would not be here. Would they have held a memorial for us? No.”

The U.S.S. Missouri is now docked in Honolulu. In 2001, several members of my family flew there to meet with the descendants of the kamikaze who tried to destroy the battleship. Together, our families participated in a Japanese kencha tea ceremony on the U.S.S. Missouri to honor those who had died.

In the years after Bill had retired as Commander of the U.S. Naval Forces, Far East, he often saw and wrote to those who had also served on the Missouri. In one of those letters, he wrote this: “I have a British admiral friend who told me some years ago … that he was never particularly ambitious to become a flag officer. What he truly enjoyed were individual command assignments afloat.”

Bill admits, “while I cannot quite subscribe to his denial of a desire for flag rank, I must agree that the most satisfying part of a naval officer’s career is command of a ship.… In that respect, my service on the Missouri is still a vivid one to me, because it was during war and actual combat.”

It is enduringly sad, but also a source of pride, that Uncle Dan — as both his family and his crew called him — gave his life for his country at Guadalcanal. Bill, who would live to the age of 93, never stopped mourning the loss of his older brother.

It is also a source of pride that even though Japanese forces killed his brother Dan — and tried to kill him and his crew — my great-grandfather Bill treated a Japanese enemy combatant in a way that befitted his battlefield convictions and with full awareness that had the circumstances been reversed, he would not have received the same treatment himself.

The author is the lead speechwriter for Janet Napolitano and the Director of Executive Communications at the University of California, Office of the President.