In Brokers of Culture: Italian Jesuits in the American West 1848–1919, the author, Rev. Gerald McKevitt, S.J., of Santa Clara University, writes, in part, of the tensions in the late 1800s at SI between teachers who believed in the European model of a classical education (such as Rev. Enrico Imoda, S.J., who served as SI president between 1887 and 1893) and others — McKevitt calls them “Americanists” — who believed in a modern system that favored practical courses such as bookkeeping and mineralogy. Foremost among these Americanists, ironically, was the Italian Jesuit Luigi Varsi, S.J., who served as president of Santa Clara College and Superior of the California Jesuit Mission. The chapter, below, from McKevitt’s book, offers insight into this pivotal point in SI’s history.

by Rev. Gerald McKevitt, S.J.

If President Imoda’s “rabbinical interpretation of our rules” (as [Rev. Giuseppe] Sasia put it) offended progressives, higher ups in Europe and conservatives in California applauded his rigor. Thus, when the time came to select a new superior to the California Mission in 1891, Imoda emerged as top candidate. That he had “many adversaries” was inconsequential, a backer argued; nor was it necessary that he “be able to speak in public or to the community or to the students in order to be a good superior.” What mattered was his unyielding asceticism. When elevating Imoda to the superiorship, Father General Anderledy tellingly borrowed a phrase from the Latin title of Pope Leo XXIII’s encyclical of that year. Imoda was worthy, he wrote, because the California Jesuits seemed “weakened by an enthusiasm for new things [rerum novarum] and for a freer discipline more in keeping with the temper of the times.” Traditionalists acclaimed Imoda’s elevation. “Thanks be to God,” one Italian exclaimed; “things are improving.”

If there was one aspect of Jesuit education that conservatives hoped to upgrade, it was its quality. Even liberals conceded that admission standards at the colleges had slipped. For the first time in decades, the California schools faced stiff competition from public institutions whose modern campuses, lower tuition and diverse curricula siphoned students by the thousands. Faced with an imperative need to improve, Americanists counseled compromise and patience lest the schools drive away their clientele. But conservative Europeans demanded immediate reform, which, they reasoned, meant a restoration of the ancient languages. Everyone recognized that Latin and Greek studies had declined. Even at Santa Clara, the order’s flagship college in the West, four times as many graduates took the Bachelor of Science degree as the classical Bachelor of Arts. Preference for a more vocational and utilitarian course of studies was not confined to the western states. In response to rapid industrial development, American education itself was moving away from the classical tradition. Of the nearly 6,000 students attending Jesuit colleges across the United States at this time, less than 2 percent graduated with the Bachelor of Arts degree in the classics.

Reports of Jesuits throughout the West made it clear that Cicero and Homer were more unpopular than ever. “The standard of classical studies is not very high,” a priest reported from Spokane in 1900. He ascribed the deficiency to the students’ “natural inconstancy, their dislike of the classics, their insatiable desire to make money, and because they are content with a purely commercial education.” In Denver, the Neapolitans of Sacred Heart College accepted the inevitable, making no pretense of giving primacy to Latin and Greek. “While appreciating the value of the ancient classical languages as a means of education,” we “believe that their value may easily be exaggerated and that much of the time commonly devoted to the study of them might with more profit be given to the study of the vernacular.” Hence they concluded, “The language of the school and the one to which most attention is devoted is English.”

Some California Jesuits, too, favored a conciliatory approach. Students are not disposed to “receive that education which we are ready and desirous to give,” the teacher Henry Woods wrote from San Francisco in 1884. Many pupils come from poor Irish working-class families, seeking only sufficient learning to give them a toe-hold in life. And because they are “too anxious to finish their college course when it ought to be only beginning,” a lengthy and expensive commitment to classical training was out of the question. We do what we can to promote the study of Latin and Greek, he insisted, by “discouraging, as far as prudence permits,” the commercial course. But to impose Caesar, Cicero and Vergil “as strictly as we would wish [was] impossible.” We must proceed gingerly when trying to raise the standard of education, he warned, for in precipitate action “there is the risk of seeing our classrooms emptied and our work strangled instead of being strengthened.”

Woods’s caveats were spurned. Offered an escape from the cul-de-sac created by a rigid curriculum, conservative Jesuits from the Piedmont region of Italy refused to budge. In this, they were backed by stewards in Europe. Alarmed at the unraveling of classical studies, they waged a campaign to restore Latin and Greek. Rev. Nicholas Congiato, S.J. (SI president for much of the 1860s) writing to Rome in 1884, announced that the classics had been “almost abandoned by everyone.” Responding to the alarm, Father General Anderledy ordered the Californians to do all that they could to rehabilitate traditional studies. Although Robert Kenna (left) of Santa Clara countered that Congiato exaggerated, the president had no choice but to comply with Rome’s mandate.

Stalwarts of the classics achieved their greatest victory three years later. In 1887, the two Piedmontese colleges in California announced they would hereafter grant academic degrees solely to students who enrolled in the classical course and passed examinations in Latin and Greek. Those languages, which before had been optional, were now made mandatory; the study of English was downgraded; and the non-classical Bachelor of Science degree was terminated. To encourage acceptance, President Imoda of St. Ignatius College spread a coat of sugar over the distasteful reform by offering “an absolutely gratuitous education” [— meaning free of charge —] to students enrolled in the classical course. But the experiment was short-lived. Four years later, his successor, Edward P. Allen (SI president 1893 to 1896), discovering that students could not even be bribed to study the ancient languages, abandoned the scholarship program. European authorities, however, would not permit Allen to restore the non-classical diploma. The outcome? Enrollments continued to slip, a direct result, critics maintained, of “the enforcement of the strictly classical course for degrees and the discouragement of the commercial course.”

The imposition of classics from on high unleashed an avalanche of protest. The next Mission Superior, Giuseppe Sasia, S.J. (SI president 1883 to 1887 and 1908 to 1911), drawing on his long experience in the U.S., informed Anderledy that “due to special circumstances in this country it is a very difficult thing to persuade students and their parents of the great importance … of classical studies.” Rev. Robert Kenna, S.J. (SI president 1880 to 1883), echoed Sasia’s argument in a series of sharp appeals to Rome. “Greek keeps many [students] away and also drives some away after they come here,” he told to Luis Martín. “You will never convince Californians that a knowledge of Greek is of any great importance” because American students preparing for careers in business and the professions did not need the classics. “It is a fact that many of our most successful public men are not classical scholars.” Even “the president-elect, Mr. Cleveland, is not a college graduate,” Kenna told an uncomprehending Martín. And U.S. Senator Stephen M. White, “the most popular man in California,” had earned his Bachelor of Science at Santa Clara College before the degree was eliminated. “Had he come later, we would not give him a degree.” Senator White “is a power in the land, and there are others like him who now cannot and will not come to this college.… I do not think that Saint Ignatius would refuse to reach souls unless he could do so by cramming them with Greek. I realize that my words may sound like heresy to many,” the president concluded one of his many transatlantic appeals, “but they are true all the same.”

Kenna’s laments were disregarded, however. Higher ups refused to budge, and, as predicted, enrollments persisted in their downward slide. Educational practices whose efficacy had been taken for granted for generations were indeed becoming outdated. But too few Jesuit authorities perceived either the need for change or the way in which change might be accomplished within the context of their tradition. The order’s mantra about adapting to times, places and persons did not, it seemed, enjoy universal acceptance.

Student discipline further polarized Jesuits. The old European system of strict surveillance and faculty control frustrated teachers and pupils alike. “The only difference between Santa Clara and any other prison,” quipped one alumnus, “was that classes instead of a stone quarry brought a student out of his cell for a considerable period each day.… The college rules prohibited everything but study,” he groused, “and, once enrolled, the festive young student might as well have been waiting for the [electric] chair.” Traditionalists nevertheless insisted on adhering to European conventions. During his tenure at St. Ignatius College, Enrico Imoda forbade card playing, smoking, boxing and similar breaches of discipline. When the Americanizing Luigi Varsi “allowed the boys to be taught round dances” at Santa Clara — “we must adapt ourselves to the ideas of the country,” he said — Jesuit rigorists were scandalized.

Still more ink was spilled over money matters, particularly in San Francisco where the Jesuits had fallen into a sink hole of debt in the construction of a new St. Ignatius College. By 1888, liability had grown to $1,008,511, a figure roughly equivalent to 18 times that amount today. Americans criticized the bookkeeping of septuagenarian Antonio Maraschi (left), the College’s founder and for decades the treasurer of the California Mission. Even Roman authorities feared the failing priest was embroiled in risky transactions that endangered the financial security of the entire Mission. “If there were a sudden failure,” Superior General Anderledy warned, “we would probably be entangled in all manner of law suits.” Visitor Rudolph J. Meyer too had urged more diligent bookkeeping during his inspection tour in 1889.

Conservatives conceded that Maraschi’s account ledgers were “a real mess,” but they were reluctant to dismiss the venerable patriarch and could not agree on a replacement. Knowledgeable observers said Luigi Varsi — because of his “natural talents” and the “esteem and friendship” he enjoyed with many wealthy Californians — was the only person who could “pull the College out of its financial difficulties and manage it well.” But defenders of the status quo, offended by Varsi’s liberal views, blocked his advancement. In consequence, Maraschi, old and nearly blind, soldiered on. Some priests, disgusted by superiors’ foot-dragging reluctance to retire the elderly treasurer, alleged a double standard. “If an English-speaking Father had been guilty of Fr. Maraschi’s doings,” said John Frieden (SI president 1896 to 1908), “there would have been a terrible outcry.”

….

How should celibate Jesuits relate to women? That was another topic that divided young and old, liberal and conservative. According to gendered conventions of the past, separation was the rule; but by the end of the century, the bonds of tradition were unraveling. More Catholic women were involved in church work than ever before, and in California women were moving in greater numbers from the domestic to the public realm. Coeducation, for example, had proven so successful at Stanford University by 1904 that alarmed admission officers established a ratio of three males to each female student. In this shifting environment, Jesuits such as Michael McKey or Luigi Varsi, favored more relaxed relationships with women in accord with the principle of adapting to changing times. Cichi and others, equating the rules and Constitutions of their religious order with the mores of Europe, argued for retention of the old ways, an interpretation shared by overseas gatekeepers. In 1886, Father General Pieter Beckx, instructed Jesuits to avoid conversing with women because they “are generally speaking, inconstant in their resolutions, and talk so much, that a great deal of time is wasted with them, and very little lasting fruit comes from it.” Visitor Rudolph J. Meyer, an American, though progressive in some matters, betrayed the same intolerance. Jesuits should not undertake ministries to women “easily or without sufficient reason,” he decreed in 1889. If women approached priests on their own initiative, Jesuits “should not engage in lengthy and useless chatter but should excuse themselves in short order.”

If extreme caution was the fruit of a cramped interpretation of Jesuit tradition, it was also the fruit of fear — fear of females and fear of provoking public criticism and scandal. Allegations of illicit relations between priests and nuns was a favorite theme of salacious best-sellers of the day, such as The Escaped Nun: Or, Disclosures of Convent Life. Jesuits “endeavor to make us Americans believe that they are chaste and that nuns are virtuous women,” a San Francisco newspaper charged; but “we believe … that they live lives of sin and profligacy rather than that of virtue and chastity.” Dreading false accusations, Jesuits were highly circumspect in dealing with the opposite sex. When earthquake and fire destroyed San Francisco’s St. Ignatius College in 1906, homeless clergy were temporarily offered refuge in a convent of nuns. One elderly Italian priest, Telesphorus Demasini, anguished over the invitation. “He thought it was compromising for us,” a contemporary said, “and also for the poor sisters.”

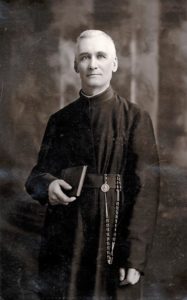

Consequently, Jesuits wagged fingers at companions judged guilty of “excessive socializing” with women whom they met in their ministry. Luigi Varsi (right), a magnetic personality with great social facility, was a frequent target of cluck-cluckers who claimed he was “continually occupied with ladies.” Giuseppe Sasia (left) defended the popular priest, pointing out that his women friends were not only “persons of outstanding piety,” but also generous benefactors of the Society. Such assurances did not assuage the wary, however. Some old timers, dipping their pens in a kind of sagacious ‘I told you so,’ recalled Jesuits of the past who had fallen in love and left the Society. “So many cases of this kind have I seen in America in the 40 or more years that I’ve been here,” Congiato warned, “that I greatly fear the coming of superiors who are not vigilant and don’t follow to the letter the wise rules left by our Father St. Ignatius.”

Unable to hammer out their differences on so many issues, turn-of-the-century Jesuits ricocheted from one crisis to the next, their effectiveness blunted by the disparities that divided them. By the time Enrico Imoda’s term drew to a close in 1896, the chasm of disagreements had so widened and deepened that even former cheerleaders conceded the reclusive superior and his coterie had done “great damage” to operations in California. In a startling about-face, Domenico Giacobbi said that Imoda’s “diffidence and sharp manner” left scarcely no one unalienated. Instead of uniting personnel in opposition to himself, his arbitrary rule had exasperated divisions.

So vast was the rift that decision-makers despaired of finding anyone to replace Imoda. Whoever was appointed superior, if acceptable to one faction, “would be quite unsatisfactory to the other,” Luis Martín observed. Unable to light on an internal candidate, the Society cast its nets widely and in 1896 appointed an outsider, John P. Frieden (left), to head the California Mission. A native of Luxembourg, he had emigrated to the U.S. as a boy and grew up in the Midwest. Now 52, Frieden had extensive academic and administrative experience, including a just-completed term as provincial of the Jesuits’ Missouri Province. Like a deus ex machina, the newcomer appeared to expectant Californians as “the salvation of the Mission.”

Settling into his San Francisco office, Frieden was appalled at what he discovered. The Californians seemed incorrigibly provincial, he told officials in Rome. Their pygmy universe centered on the San Francisco Bay Area, and they had no residence more than 55 miles distant from the next. Even more shocking, they seemed “quite satisfied to remain isolated in this corner.” “Narrow and cramped in their ideas.… several Fathers of this mission have a strange idea of life in the Society,” he wrote, revealing that his sympathies did not lie with defenders of the status quo. These misguided souls “are conceited enough to imagine that the true spirit of the Society is preeminently in California, not in any other part of the United States.” They “imagine that they are doing all that is expected of them if they devote full time to their spiritual exercises. For the rest, they shut themselves so completely off from the outside world as if our vocation were monastic, solely contemplative, and not actively apostolic.” The damage resulting from this distorted grasp of Jesuit life was far-reaching. Our young men are being “trained on wrong lines,” Frieden went on. “We are losing our hold on the people; men especially are drifting away from us.” If Imoda and his advisors had “deliberately tried to break down Jesuit work and Jesuit standing in the city of San Francisco and in California,” he concluded, “they could not have chosen better means. … We must bestir ourselves to regain the hold which we used to have on the people years ago, and which simply passed away during the past 10 or 12 years.”

Frieden attempted to chart a new course by appointing progressives to positions of authority. But his cranky personality and reversal of long-standing practices inevitably antagonized the old guard, prompting alarmists like Cichi to declare that “Father Frieden and his Irish consultors had destroyed the Mission.” Meanwhile, Americanizers cheered his reforms. And his firm-handed leadership during the San Francisco Earthquake and Fire of 1906, which destroyed St. Ignatius College, won him many admirers.

But when time came to find a successor, the old conundrum reappeared. Whom to appoint? “There is no one in California that could in the near future govern the Mission,” Frieden himself advised Rome. However, if the General was willing to merge the Rocky Mountain and California missions — a plan that had been under consideration for several years — a solution was at hand. There was an experienced administrator in Oregon, Frieden recounted, who could fill the bill. Thus it was that the two jurisdictions were reunited, and Georges de la Motte, a 46-year-old wunderkind from Alsace and eminent alumnus of Woodstock College, became head of Jesuit operations on the West Coast. A man of uncommon intelligence and culture, this highly respected missionary was well equipped for his new role. As restrained and diplomatic as Frieden was blunt and imperious, De la Motte integrated the two missionary jurisdictions and calmed the dyspeptic Californians, a task eased by attrition through death of some of the old guard. At the same time, he tackled a set of challenges unique to the Rocky Mountain Mission.

If you are interested in purchasing Brokers of Culture to learn more about Jesuits in the West,go to Stanford University Press’s website or to the Jesuit Retreat Center bookstore in Los Altos.